Fatigue Is a Means, Not the Goal.

Many people treat fatigue as a badge of honour.

If they’re not wrecked after training, they feel like they haven’t worked hard enough.

But fatigue isn’t the goal. It’s simply a byproduct of effective training, a sign that your body has been challenged and now needs to recover. The real progress happens after you rest, not during the exhaustion itself.

The Fine Dance: Stimulus → Fatigue → Recovery → Supercompensation

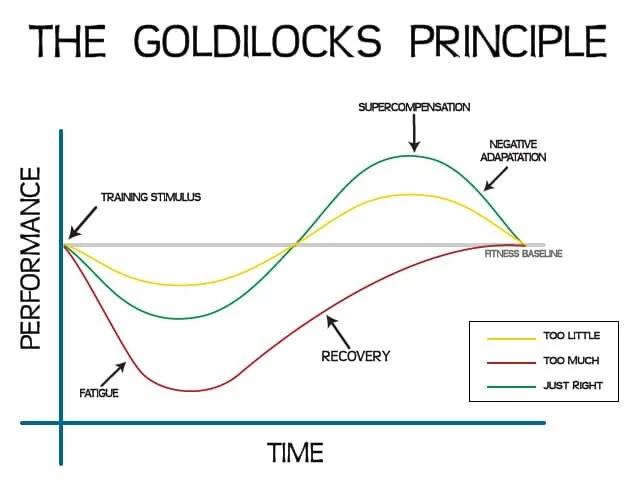

Every workout applies a stimulus, a stress your body must respond to. This stress causes fatigue, a temporary dip in performance as your muscles, energy systems, and nervous system become depleted.

During recovery, your body works to restore balance: muscles repair, energy stores refill, and the nervous system resets. Then comes supercompensation, your body adapts by becoming slightly stronger, more resilient, or more efficient than before.

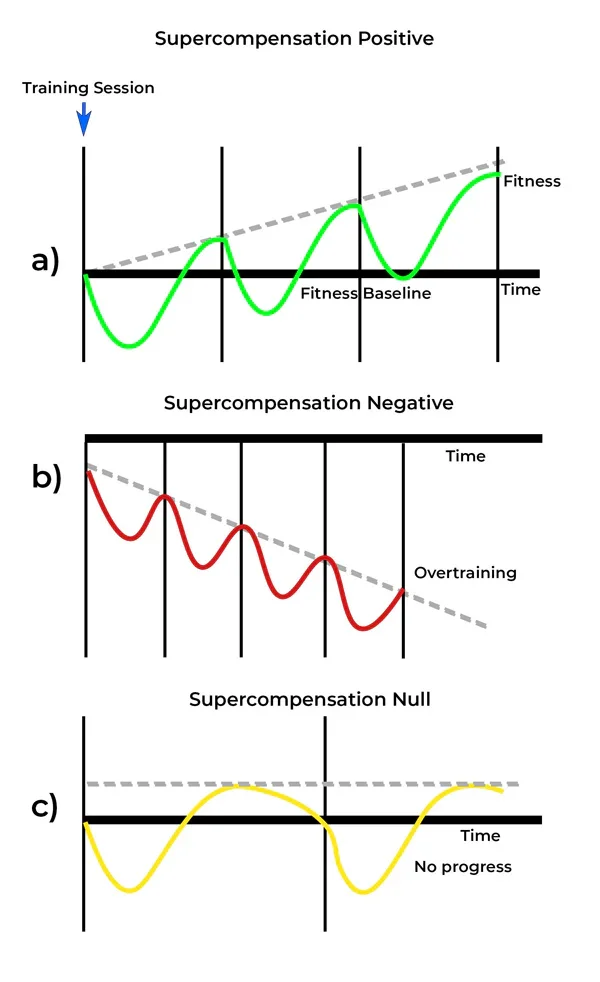

If you train again at the right time, when you’ve recovered but before the adaptation fades, the cycle continues upward. Mistime it, and progress stalls: train too soon, and you interrupt recovery; wait too long, and the gains fade before the next stimulus.

This is why fatigue isn’t something to chase for its own sake; it’s something to manage.

1. The Ideal Ratio: Productive Fatigue

In a well-structured program, fatigue is introduced progressively and intentionally. Some sessions are harder, creating meaningful stress, while others are lighter, allowing recovery. Over time, this creates accumulation phases, blocks of training designed to build fatigue and set the stage for greater adaptation.

These are then followed by deload or recovery phases, where training volume or intensity drops to let the body catch up and supercompensate.

For example, a four-week strength block might include three progressively harder weeks followed by one easier week. This pattern allows fatigue to build and then release, leading to visible performance improvements without burnout.

Chasing fatigue can make sense for someone who trains sporadically, say, once or twice a week. In that case, there’s plenty of recovery time between sessions, so pushing hard occasionally won’t hurt. But if you’re training five or six times a week, and your coach tries to “kill you” every time, that’s not intensity, that’s poor programming.

2. No Fatigue: No Stimulus, No Progress

At the opposite end, a complete absence of fatigue usually means the training stimulus is too weak to provoke adaptation. If every workout feels easy, your body has no reason to change.

Think of someone who lifts the same weights every week or cycles at the same comfortable pace; they might feel good, but they won’t get stronger or fitter. In this scenario, fatigue isn’t something to fear; it’s a sign you’ve asked your body to do something new.

A good plan doesn’t avoid fatigue; it creates manageable amounts of it.

3. Too Much Fatigue: When Stress Becomes a Roadblock

On the other hand, too much fatigue leads to stagnation or decline. Training hard without sufficient rest builds up residual fatigue that blunts performance, slows recovery, and increases injury risk.

It’s a trap many fall into — thinking that if hard is good, harder must be better. But chronic fatigue is the enemy of consistency. If every session leaves you destroyed, your body never gets the chance to adapt if it’s too busy surviving.

That’s why elite athletes periodize their training: they push hard in planned phases, then deliberately back off to let the gains manifest.